- Home

- Deutschland Tour 2021

- Stage 2. Sangerhausen – Illmenau

Stage 2. Sangerhausen – Illmenau

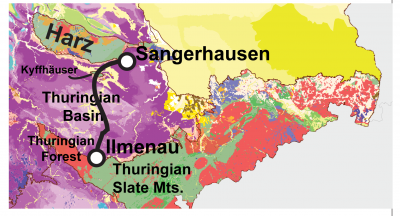

The second stage starts in Sangerhausen, in the foothills of the southern Harz. The present-day Harz mountains is the leftover of a large Himalayan-style mountain range that stretched over almost all of central and southern Europe some 350 to 300 million years ago. The Harz literally lied in the collision zone when two large continents collided around the equator to form the supercontinent Pangea. Over the many millions of years that elapsed since then, the mountain range eroded down to hills. These hills can be found all around Europe: the Central Massif in France, the Spanish Meseta Central, the Ardennes-Eifel region and the Rhenish Massif. Since the Harz represents the remains of a 300 million-year-old mountain range, we mostly find rocks there that are older than that date. In Sangerhausen, however, we are on the foothills just outside the Harz and one finds Triassic Bundsandstein in the subsurface. The Bundsandstein has an age of about 250 million years and thus formed at the time when the formation of supercontinent Pangea was concluded. An extremely dry climate then prevailed over Germany, and the sedimentary environment probably looked similar to what we see today in the dry lakes of Nevada, Bolivia or Iran. The Bundsandstein consists of red-coloured sandstones with gravel-sized clasts, and has been deposited in the form of large alluvial fans, coming of the mountainous terrain of Pangaea.

In Sagerhausen, we stand at the northern edge of the Thuringian Basin. You can think of the Thuringian Basin as a pile of dishes with Erfurt in the middle. All the dishes were deposited during the Triassic, but there is a clear hierarchy among them. The oldest dish also has the largest diameter and sits at the bottom of the pile: This is the Bundsandstein. On top of that is a slightly younger plate consisting of Muschelkalk limestone. On top of that is then an even younger and smaller plate of Keuper dolomites, shale and evaporite rocks. Over the course of geologic time, some cracks, tears and folds did appear in the pile of dishes as chunks of sedimentary rock shifted and faulted under tectonic influence. Nevertheless, the pile of dishes remains a useful analogy when considering that the second stage makes a north-to-south cross-section through the Thuringian Basin.

The first significant hill of the second stage is one of those tectonically displaced shards that pierced our pile of dishes: The Kyffhäuser (473 m above sea level). On the geologic map, the Kyffhäuser appears as an enclave of older Paleozoic rocks in the north of the Thuringian Basin, which is otherwise dominated by Triassic rocks. The riders have to climb up these ancient rock layers, which we would normally expect to find only in the Harz. Yet, the colliding Earth plates that also started forming the Alps some 95 million years ago, some deep fractures in the Earth’s crust of Central Europe appeared. The ancient rock layers that make up the Kyffhäuser hill came to the surface along such a fracture at the northern rim of the hill, and thereby pierced through the Triassic pile of dishes.

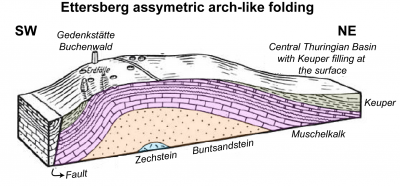

The second hill of the day brings the riders to the Buchenwald concentration camp on the Ettersberg. The Ettersberg corresponds to an asymmetric arch-like fold in the Muschelkalk in the center of the Thüringian Basin. The Muschelkalk actually belongs to the second upper plate in the stack, yet due to the strong folding of the layers near Ettersberg, the Muschelkalk pierces through the Keuper strata above. The riders climb to an elevation of about 480 m via the northern flank, and then descend via the steeper southern flank to the city of Weimar. The rest of the stage takes us over a slightly sloping terrain to the southern edge of the Thuringian Basin. The finish line in Ilmenau lies exactly on the border between the Thurigian Basin and the Thuringian Forest. Geologically speaking, this is the border between the sedimentary rocks of the Triassic in the north and much older metamorphic and magmatic rocks in the south. You’ll hear more about those tomorrow! My secret tip for today’s stage: Nils Politt.