Page path:

- Graduate School GLOMAR

- PhD student reports

- Field Campaigns

- Amanda Ford

Amanda Ford

Report of GLOMAR PhD student Amanda Ford about her field campaign in Fiji, August 2015 - April 2016

In August 2015, a team of ecologists comprising our junior workgroup leader, a postdoc, three ISATEC students and myself packed our bags, 400+ kg of diving and research gear and headed to the Pacific. After 40 hours of travel, we were finally reunited in Fiji with the two other social science PhD candidates from our project who had already been conducting their work for several months.

The first couple of weeks were spent selecting sites, introducing ourselves to the local communities and asking permission from them to carry out work on their reefs (a process that generally involves consuming large amounts of Kava). The coastal area in front of Fijian villages traditionally comes under the customary tenure of adjacent communities, and acts as their fishing ground (qoliqoli). Therefore, it is critical to work alongside local communities and to have their permission for any work that you intend to do.

The project that my PhD is part of is "Resilience of South Pacific coral reef socio-ecological systems in times of global change" (REPICORE). Thus the ecology team was particularly interested in looking within the community-managed tabu (no-take) areas of the qoliqolis, as well as looking as the effects of small fishing villages on reef ecosystems. My particular project focuses on benthic community function and dynamics, and the two main aims of my work were to; (i) improve monitoring of coral reefs to understand reef trajectories and their recovery potential, and (ii) to assess how water quality shapes functional compositions or coral communities, and the effect on associated resilience to key stressors. We ended up selecting three areas to work in; near to the capital Suva where us and our equipment would generally be based, on Beqa Island, and on the island of Ovalau.

Over the following months, we undertook hundreds of dives, moved hundreds of kilos of gear around between all of our sites (sometimes in quite small boats on concerningly rough seas), spent several weeks staying on the two islands becoming part of our host families, obtained some fascinating infections and an array of bites from mosquitos to bed bugs, experienced rain like none of us have before (and I am from the UK) and rescued a stray puppy! We got to dive on some great reefs, and also some not so great ones. By measuring a huge assortment of processes within both the fish and benthic communities, we began to obtain a good picture of reef status across our sites. Indeed, although baselines surveys of obvious indices for no-take area effectiveness (i.e. fish biomass and fleshy algae cover) remained unaffected by management, quantification of bare substrate condition such as turf canopy length and coral recruitment showed that no-take areas were making some difference within the benthos.

Although we thought we had been lucky and escaped the devastating effects of the 2016 El Niño event, in February the water around Fiji’s coast started to warm up. Reports started to emerge of coral bleaching and fish kills which followed depleted oxygen levels at low tide when water was reaching > 35°C. Then to make matters worse, on the 20th February, category 5 Cyclone Winston hit Fiji with full force, leaving tens of thousands of people homeless. Suva was not in the centre of the path of the storm, and so avoided the worst damage, but we had a curfew for a few days, no water for a week and no power for two weeks – not good when you have a freezer full of frozen samples! As soon as the communities were back to normal, I got back out and resurveyed most of our sites to measure the bleaching severity and prevalence, and to see if Cyclone Winston had caused any damage. Fortunately, it seemed our reefs had remained mostly unscathed by the cyclone, but the bleaching effects were significant, with up to 80% of the coral community exhibiting signs of bleaching at some of our sites.

Finally, we arrived back in Germany after nearly nine months with an overload data that could keep us all busy for several months! Now it is time to sit down and work through it as there is only a few months until I have to hand in my thesis...

I would like to thank the BMBF for funding this work through the REPICORE project, and to my supervisors Dr. Sebastian Ferse, Dr. Maggy Nugues, Dr. Albert Nyström and Prof. Dr. Christian Wild for their ongoing advice and support. Thanks also to our local collaborators at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Fiji and the University of the South Pacific (USP). Finally, a huge thank you to all of the communities for their permission to carry out work on their land and for their warmth and generosity over the months.

The first couple of weeks were spent selecting sites, introducing ourselves to the local communities and asking permission from them to carry out work on their reefs (a process that generally involves consuming large amounts of Kava). The coastal area in front of Fijian villages traditionally comes under the customary tenure of adjacent communities, and acts as their fishing ground (qoliqoli). Therefore, it is critical to work alongside local communities and to have their permission for any work that you intend to do.

The project that my PhD is part of is "Resilience of South Pacific coral reef socio-ecological systems in times of global change" (REPICORE). Thus the ecology team was particularly interested in looking within the community-managed tabu (no-take) areas of the qoliqolis, as well as looking as the effects of small fishing villages on reef ecosystems. My particular project focuses on benthic community function and dynamics, and the two main aims of my work were to; (i) improve monitoring of coral reefs to understand reef trajectories and their recovery potential, and (ii) to assess how water quality shapes functional compositions or coral communities, and the effect on associated resilience to key stressors. We ended up selecting three areas to work in; near to the capital Suva where us and our equipment would generally be based, on Beqa Island, and on the island of Ovalau.

Over the following months, we undertook hundreds of dives, moved hundreds of kilos of gear around between all of our sites (sometimes in quite small boats on concerningly rough seas), spent several weeks staying on the two islands becoming part of our host families, obtained some fascinating infections and an array of bites from mosquitos to bed bugs, experienced rain like none of us have before (and I am from the UK) and rescued a stray puppy! We got to dive on some great reefs, and also some not so great ones. By measuring a huge assortment of processes within both the fish and benthic communities, we began to obtain a good picture of reef status across our sites. Indeed, although baselines surveys of obvious indices for no-take area effectiveness (i.e. fish biomass and fleshy algae cover) remained unaffected by management, quantification of bare substrate condition such as turf canopy length and coral recruitment showed that no-take areas were making some difference within the benthos.

Although we thought we had been lucky and escaped the devastating effects of the 2016 El Niño event, in February the water around Fiji’s coast started to warm up. Reports started to emerge of coral bleaching and fish kills which followed depleted oxygen levels at low tide when water was reaching > 35°C. Then to make matters worse, on the 20th February, category 5 Cyclone Winston hit Fiji with full force, leaving tens of thousands of people homeless. Suva was not in the centre of the path of the storm, and so avoided the worst damage, but we had a curfew for a few days, no water for a week and no power for two weeks – not good when you have a freezer full of frozen samples! As soon as the communities were back to normal, I got back out and resurveyed most of our sites to measure the bleaching severity and prevalence, and to see if Cyclone Winston had caused any damage. Fortunately, it seemed our reefs had remained mostly unscathed by the cyclone, but the bleaching effects were significant, with up to 80% of the coral community exhibiting signs of bleaching at some of our sites.

Finally, we arrived back in Germany after nearly nine months with an overload data that could keep us all busy for several months! Now it is time to sit down and work through it as there is only a few months until I have to hand in my thesis...

I would like to thank the BMBF for funding this work through the REPICORE project, and to my supervisors Dr. Sebastian Ferse, Dr. Maggy Nugues, Dr. Albert Nyström and Prof. Dr. Christian Wild for their ongoing advice and support. Thanks also to our local collaborators at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Fiji and the University of the South Pacific (USP). Finally, a huge thank you to all of the communities for their permission to carry out work on their land and for their warmth and generosity over the months.

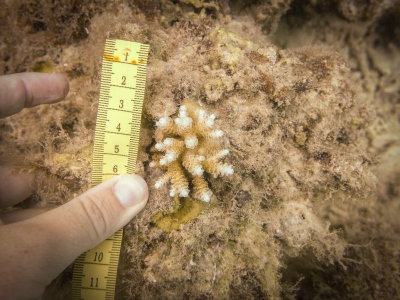

Coral recruitment tiles were left at four of our sites from October 2015 until January 2016, when they were collected, bleached and assessed under a microscope