Page path:

- Home

- Discover

- Media Releases

- Media Releases 2016

- Tiny marine animals conquer Mediterranean beaches

Tiny marine animals conquer Mediterranean beaches

Sep 6, 2016

The preservation of species diversity during times of climate change requires that individual species will be able to adapt to new environmental conditions, especially warmer temperatures. How quickly adaptation occurs is vital. Coral reef habitats react very sensitively to change because many of their inhabitants live in symbiosis with algae. Increasing temperatures cause the corals to lose their algae, which results in bleaching of the corals. A team of German and Israeli scientists, in field and laboratory investigations, have now shown that some tiny marine animals called foraminifera can survive extremely warm conditions without losing their algae. The researchers, under the leadership of Christiane Schmidt of MARUM, the Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen, have published their results in the journal Scientific Reports.

The Mediterranean is a model region for researchers. It is particularly suitable for studying the impacts of climate change on coastal ecosystems. Observations and prognoses indicate that the eastern Mediterranean is warming relatively rapidly. Species that cannot adapt in this region have to migrate to cooler areas to the west or they die out.

For this study, Dr. Christiane Schmidt and Prof. Dr. Michal Kucera of MARUM, with their Israeli colleagues, investigated small marine animals from the coast of Israel. These organisms, called foraminifera, live in symbiosis with single-celled siliceous algae. The algae carry out photosynthesis, providing the foraminifera with food and promoting the growth of their calcareous shells. Foraminifera produce calcium carbonate and are thus considered, like the corals, to be engineers of the marine ecosystems.

The German-Israeli team was able to take advantage of the effects of the large-scale operation at the power plant at Hadera, whose discharge of cooling water warms the sea water. Here the temperature is raised in a kilometer-long strip around the power station. A species of foraminifera was discovered in this area that retains its algal assemblage even in the summer when temperatures exceed 36 degrees Celsius. The scientists were able to confirm that this species of foraminifera is also tolerant of increased temperatures outside of the warm coastal area at Hadera. “In the laboratory we were able to show that the algae carry out photosynthesis at 36 degrees Celsius and the foraminifera grow, a sign that this species can withstand these temperatures over the long term,” explains Christiane Schmidt. Instruments deployed by the team along the coast indicate that natural temperatures throughout the year do not exceed 32 degrees.

“That means that this species is better adapted to warming than most other marine animals with algal assemblages,” summarizes the Bremen geoecologist. Under conditions of long-term warming they were thus able to take over the coastal habitat of the eastern Mediterranean. The scientists believe that the investigated species, Pararotalia calcariformata, is an invasive species. They assume that the tolerance to heat is a trait that originated in the Pacific. “Foraminifera could thus also be winners in the struggle against climate change in other regions,” concludes Michal Kucera.

Christiane Schmidt intends to continue researching the causes for heat tolerance and to address the question of how the adaptation evolved. This requires a combination of field results with studies in the laboratory. She asserts that, “This will allow us to better assess how species in the sensitive coastal habitat will react to global change.”

The Mediterranean is a model region for researchers. It is particularly suitable for studying the impacts of climate change on coastal ecosystems. Observations and prognoses indicate that the eastern Mediterranean is warming relatively rapidly. Species that cannot adapt in this region have to migrate to cooler areas to the west or they die out.

For this study, Dr. Christiane Schmidt and Prof. Dr. Michal Kucera of MARUM, with their Israeli colleagues, investigated small marine animals from the coast of Israel. These organisms, called foraminifera, live in symbiosis with single-celled siliceous algae. The algae carry out photosynthesis, providing the foraminifera with food and promoting the growth of their calcareous shells. Foraminifera produce calcium carbonate and are thus considered, like the corals, to be engineers of the marine ecosystems.

The German-Israeli team was able to take advantage of the effects of the large-scale operation at the power plant at Hadera, whose discharge of cooling water warms the sea water. Here the temperature is raised in a kilometer-long strip around the power station. A species of foraminifera was discovered in this area that retains its algal assemblage even in the summer when temperatures exceed 36 degrees Celsius. The scientists were able to confirm that this species of foraminifera is also tolerant of increased temperatures outside of the warm coastal area at Hadera. “In the laboratory we were able to show that the algae carry out photosynthesis at 36 degrees Celsius and the foraminifera grow, a sign that this species can withstand these temperatures over the long term,” explains Christiane Schmidt. Instruments deployed by the team along the coast indicate that natural temperatures throughout the year do not exceed 32 degrees.

“That means that this species is better adapted to warming than most other marine animals with algal assemblages,” summarizes the Bremen geoecologist. Under conditions of long-term warming they were thus able to take over the coastal habitat of the eastern Mediterranean. The scientists believe that the investigated species, Pararotalia calcariformata, is an invasive species. They assume that the tolerance to heat is a trait that originated in the Pacific. “Foraminifera could thus also be winners in the struggle against climate change in other regions,” concludes Michal Kucera.

Christiane Schmidt intends to continue researching the causes for heat tolerance and to address the question of how the adaptation evolved. This requires a combination of field results with studies in the laboratory. She asserts that, “This will allow us to better assess how species in the sensitive coastal habitat will react to global change.”

Publication:

Christiane Schmidt, Danna Titelboim, Janett Brandt, Barak Herut, Sigal Abramovich, Ahuva Almogi-Labin, Michal Kucera:

Extremely heat tolerant photo-symbiosis in a shallow marine benthic foraminifera.

Published in: Scientific Reports.

DOI: 10.1038/srep30930

Christiane Schmidt, Danna Titelboim, Janett Brandt, Barak Herut, Sigal Abramovich, Ahuva Almogi-Labin, Michal Kucera:

Extremely heat tolerant photo-symbiosis in a shallow marine benthic foraminifera.

Published in: Scientific Reports.

DOI: 10.1038/srep30930

Contact:

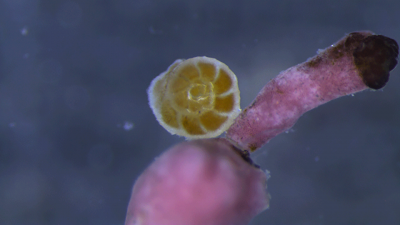

Rocks near the power plant in Hadera (Israel) are the habitat for the foraminifera. They can survive the extreme temperatures produced by warm water discharged from the plant.

Photo: MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen; C. Schmidt

The natural habitat of foraminifera in Nachsholim National Park. The tolerance to extreme temperatures was also documented here.

Photo: MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen; C. Schmidt

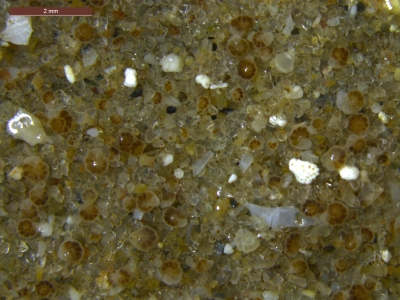

A sediment sample from a water depth of five to seven meters near the Hadera power station shows a very high occurrence of the heat-tolerant species Pararotalia calcariformata.

Photo: MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen; C. Schmidt