- Home

- Discover

- Archive News

- News 2020

- impact deep-sea mining

Simulated deep-sea mining affects ecosystem functions at the oceanfloor

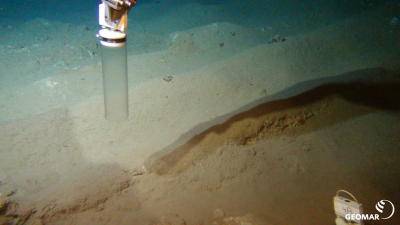

As part of the project “MiningImpact”, the Max Planck Institute in Bremen has now taken a closer look at the smallest seabed inhabitants and their performance. The present study shows that microorganisms inhabiting the seafloor would also be massively affected by deep-sea mining. The team led by Antje Boetius, group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology and director at the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, travelled to the so-called DISCOL area in the tropical East Pacific, about 3,000 kilometers off the coast of Peru, to investigate conditions of the seafloor as well as the activity of its microorganisms. Back in 1989, German researchers had simulated mining-related disturbances at this site by ploughing the seabed in a manganese nodule area of three and a half kilometers in diameter with a plough-harrow, 4,000 meters under the surface of the ocean. 26 years later, the plough tracks on the ocean floor are still clearly visible.

Compared to undisturbed regions of the seafloor, only about two thirds of the bacteria lived in the old tracks, and only half of them in fresher plough tracks. The rates of various microbial processes were reduced by three quarters in comparison to undisturbed areas, even after a quarter of a century. “Our calculations have shown that it takes at least 50 years for the microbes to fully resume their normal function,” says first author Tobias Vonnahme.

Jürgen Titschack from MARUM collected the computer tomography data of the investigated sediments for the study and led their evaluation. “The natural habitat of microorganisms is the sediment on the seafloor. However, deep-sea mining destroys the natural sediment structure and thus profoundly changes the microorganisms’ habitat. The three-dimensional CT-based characterization of the sediments allows these changes to be visualized and in some cases quantified – an important background information for all further analyses.”

Contact:

Dr. Jürgen Titschack

Marine Sedimentologie

Email: [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Tobias R. Vonnahme, Massimiliano Molari, Felix Janssen, Frank Wenzhöfer, Matthias Haeckel, Jürgen Titschack, Antje Boetius (2020): Effects of a deep-sea mining experiment on seafloor microbial communities and functions after 26 years. Science Advances. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz5922

Press release Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology